At the Camp David G8 summit in 2012, President Obama announced an $8 billion initiative called the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition. The initiative promised to inject much-needed money into rural communities in Africa. Yet the $2 billion of U.S. taxpayers’ money committed by President Obama to the New Alliance is being used to support large agribusiness projects – some of which are forcing poor farmers off their land in countries like Tanzania.

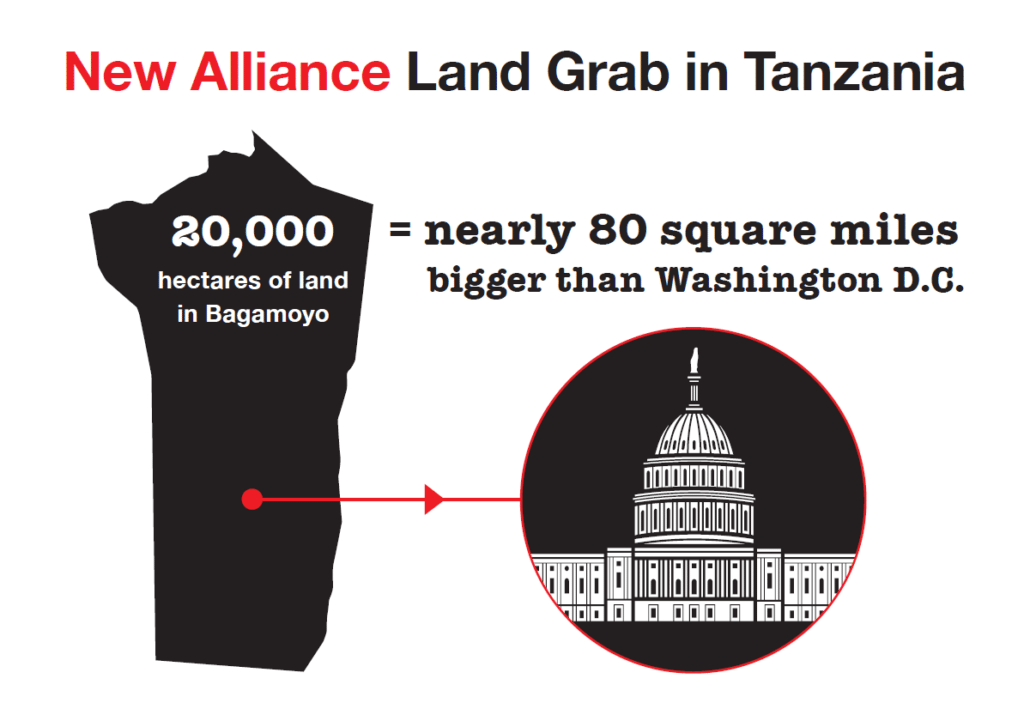

One of the first of these projects to break ground was by a Swedish-owned company called EcoEnergy. The company planned to start a sugarcane plantation that would cover 20,000 hectares of land – an area of land bigger than Washington D.C.

The company arrived in Bagamoyo claiming that its project would inject $45 million a year into the local economy. But local people were skeptical.

Up to 1,300 people faced eviction for the plantation. They were going to be forced to leave their homes and land – their main source of livelihood – without being consulted or properly compensated.

ActionAid had been working in the area for a number of years and the community asked us to work with them to protest the project and claim their rights to land.

Our research strongly contradicted EcoEnergy’s claims that its project would bring significant financial gain to the area. We found that EcoEnergy had inflated the amount of money it would put into the local economy by more than $30 million per year. With the plantation likely to produce sugar for ethanol, both the product and the profits looked set to leave the country.

One of the ways that EcoEnergy claimed the project would benefit the communities is through an “outgrower” scheme. Under the plan, farmers would grow sugarcane and supply the company at an agreed price. But this would be a huge risk for the farmers, who would have needed to take out loans equivalent to $16,000 per person, or 30 times the minimum annual agricultural salary in Tanzania.

EcoEnergy estimated that it would take at least seven years for the farmers to pay back the loan and make a profit. But they would have faced higher costs, as the food they used to grow themselves would have to be purchased, and they would have to pay for housing for their families elsewhere.

The project was one of more than 20 large land projects in the pipeline in Tanzania alone, with the New Alliance creating the same huge demand for land in many other African countries.

In May 2016, we heard the Tanzanian government had decided to shelve plans for a sugar and biofuels project in Bagamoyo. Our staff in Tanzania worked closely with local people and experts around the world to document the communities’ land claims and show how their land and livelihoods were at risk from the project. Our teams also met with representatives from the Tanzanian and U.S. governments, and our supporters signed a petition calling on the Obama administration to withdraw its support to the New Alliance.

There also seems to have been a major scaling back of the Tanzanian government’s plan called Big Results Now. The plan was backed by the New Alliance and announced that the Bagamoyo site and 15 others would be developed for the global sugar and biofuels markets. In response to questions from parliament, the Tanzanian Prime Minister stated that the development of sugar projects would go forward in at least four regions in Tanzania.

Hopefully this is a sign that the Tanzanian government has a new commitment to a participatory planning processes with communities. Community-based decision-making can assess what types of development projects will help local communities maintain control over and benefit sustainably from their natural resources, while increasing the supply of nutritious food locally and regionally.

Even though the project has been shelved, the legal status of the land that was targeted by the company in Bagamoyo is still not clear. While some of the land included in the former project has been recognized as belonging to local villages, a part of the land known as Razaba remains in question.

There are many pastoralists and people with farming skills in Tanzania who need land, and their claims should be prioritized ahead of outside investors. That’s why we continue to work closely with communities around the world to make sure their rights to land are upheld, and played a leading role in getting a series of guidelines approved by the United Nations that will help guarantee land rights for vulnerable and marginalized people around the world.